Congenital hand differences most often do not have definitive explanation. This makes answering “What happened to your hand?” a sometimes challenging question to answer. Children use their hands for many social activities, like hand clap games, holding hands, hugging, gesturing, eating, carrying things, playing games, and writing; which means hands that appear different then expected are often noticed by others.

STEPS and RYR are communication tools developed by the Phoenix Burn Society to help empower children to develop a response to “What happened to your hand?” questions and staring. As your child begins the transition to pre-school and kindergarten, or if you child is feeling anxious about people asking questions and/or staring try out STEPS and RYR.

STEPS*

STEPS is a tool you can use to help your child build confidence and teach others how to interact with them. It may take practice for it to become part of your child’s daily life.

The principle behind STEPS is that your child can control the image they choose to present to others, and the conversation they have with others about their CHD.

Try practicing STEPS with your child, or have your child practice in front of a mirror.

S = Self Talk – Prepare a list of positive messages to tell yourself, for example:

- I love and accept myself for the way I am

- My hand difference is a part of me but not all of me

- I am beautiful

- I meet people easily and they want to be my friend

T = Tone of voice – Be mindful of they way you answer questions,

- Friendly

- Warm

- Enthusiastic

E = Eye Contact

- Look people in the eye, even if only for a few seconds

P = Posture

- Head raised

- Shoulders back

- Rib cage lifted

S = Smile

Rehearse Your Response (RYR)*

RYR is a tool your child can use to navigate conversations with people who are new to them.

Sometimes children want to tell their whole story and do not mind attention and questions. Other times children want the conversation to end quickly.

To help speed up the conversation, your child can learn (by practicing with you) a 3-sentence response to the question “What happened to your hand?” This 3-sentence response can be practiced with STEPS (above) until your child feels comfortable and confident.

Remember to help your child understand that they are in control of the conversation, and when they no longer want to answer questions they can say “That’s all I want to talk about, thank you for understanding”.

Examples of a 3 sentence response to the question: “What happened to your hand?”

- Address the nature of the condition i.e “I was born this way”, “It might look different than you expect”, “I had surgery when I was a baby”. Another way to address the nature of the condition is to use humor by saying things like “It got bitten off by a shark”, “I was wrestling a bear” or “An alligator tried to steal my cookies.” Help your child develop whatever response best fits their personality.

- Mention how they are doing now, e.g. “I am going to have surgery” or “I can play basketball”

- End the conversation: “Thank you for asking”.

Examples of 3 sentence responses include:

- “I was born like this and I had a surgery when I was a baby. I can do everything I need to, it might look a little different than you might expect. Thank you for asking.”

- “I was born this way, I can do baton and play volleyball. Thank you for asking.”

When someone continues to ask your child questions and your child does not want to answer, help empower them to say something like: “That is all I want to talk about right now, thank you for understanding”, then smile and physically leave the conversation.

Encourage your child to practice in front of a mirror or with siblings or friends, until they feel comfortable and prepared.

Sometimes people are unfamiliar with a CHD and have a difficult time understanding it. They don’t know how to interact with someone with a CHD. They may struggle with the “right” words to use and may use terms that feel offensive to people with a hand difference.

Your child can respond with comments such as “Let’s try that again” or “How about we try another word” or your child can say: “The words I like to use are.. (limb difference, small hand, nubbin etc.), I would appreciate if you used these terms too.”

We encourage you to explore how your child wants to talk about their CHD. If you have concerns please talk with your Pediatric Hand Team, they are here to help!

Staring*

Yes, looking different draws attention. Most people look out of curiosity or concern. Very few stare to be rude.

We may not be able to change people’s reactions to seeing someone with a CHD. But we can help children manage their reactions to staring.

- You and your child are in control of the interaction. Use the STEPS and RYR tools to navigate social interactions and help teach others how to interact with your child.

- If your child sees someone staring at them they can use their STEPS tools and confidently say, “Hi, how are you?” or any other form of small talk. The person staring will usually respond in a friendly way and stop staring. By smiling and speaking to someone who is staring, your child takes control of the interaction, and potentially teaches the staring person an important lesson: a person with a CHD is a normal person, who happens to have CHD.

*Material copyright Phoenix Society for Burn Survivors. Adapted for CHD. Used with permission.

If you find that social interactions have escalated to teasing or bullying behaviors please talk with the Pediatric Hand Team, or the professionals in the community where the bullying or teasing behaviors are occurring.

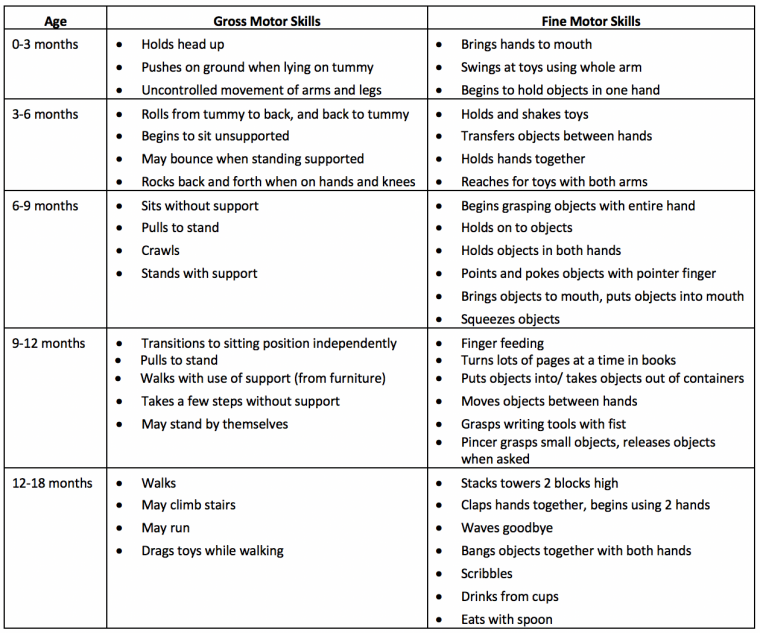

Developmental milestones are based on the anticipated development of a child born at term to 5 years. They serve to measure brain development by monitoring the age at which children typically start to do different tasks. It is important to clarify that not all children hit these milestones within these time frames or they may skip milestones. There is a lot of variation on how children develop.

Developmental milestones are based on the anticipated development of a child born at term to 5 years. They serve to measure brain development by monitoring the age at which children typically start to do different tasks. It is important to clarify that not all children hit these milestones within these time frames or they may skip milestones. There is a lot of variation on how children develop.

Hands are often used socially: for hand-holding, hugging, shaking hands, high fives, playing, eating, and gesturing while talking. They are a visible part of the body, and hand differences are often noticed by others. The first time a person ever sees a CHD may be when they meet your child. However, for your child, managing and navigating interactions with other people are daily tasks.

Hands are often used socially: for hand-holding, hugging, shaking hands, high fives, playing, eating, and gesturing while talking. They are a visible part of the body, and hand differences are often noticed by others. The first time a person ever sees a CHD may be when they meet your child. However, for your child, managing and navigating interactions with other people are daily tasks.

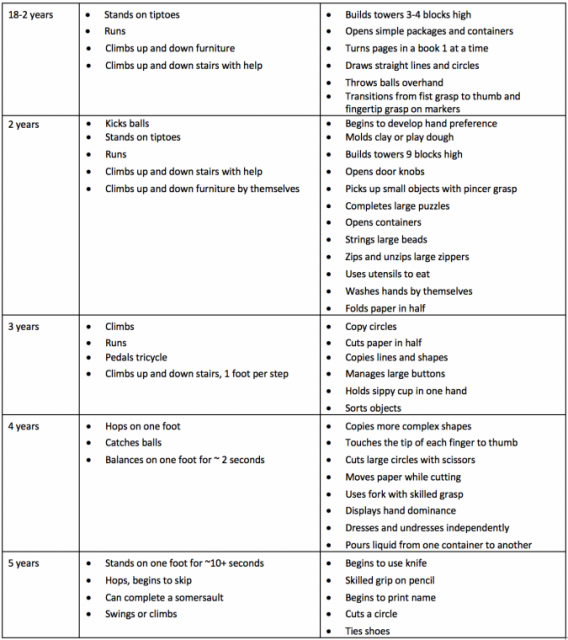

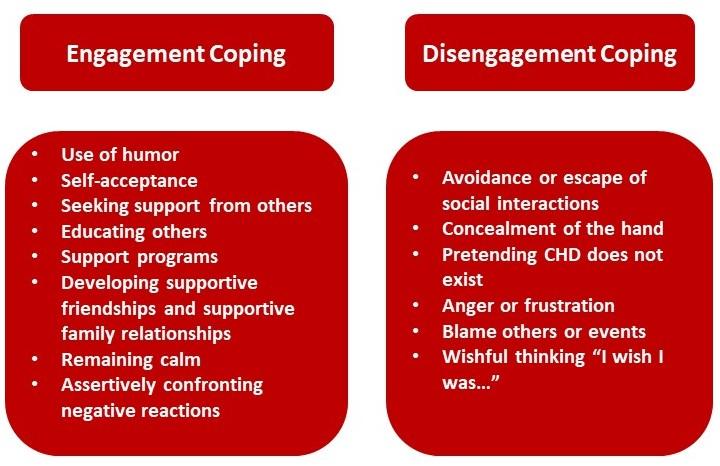

Children with CHD tend to undergo self-awareness and self-acceptance processes related to their social and emotional development. The following anticipatory guidance may help you anticipate and understand social and emotional concepts that your child may experience. Keep in mind every child is unique; your child may or may not experience components listed or may experience them in a different order.

Children with CHD tend to undergo self-awareness and self-acceptance processes related to their social and emotional development. The following anticipatory guidance may help you anticipate and understand social and emotional concepts that your child may experience. Keep in mind every child is unique; your child may or may not experience components listed or may experience them in a different order.

Help your child to develop a positive self-concept and pride in their CHD. This is done by reinforcing activities or skills they are “good at,” and encouraging them to try and experience success with moderately challenging activities (e.g. climbing a rock wall). We strongly recommend summer camps for children with limb differences (

Help your child to develop a positive self-concept and pride in their CHD. This is done by reinforcing activities or skills they are “good at,” and encouraging them to try and experience success with moderately challenging activities (e.g. climbing a rock wall). We strongly recommend summer camps for children with limb differences (

A “social script” is a way people learn to navigate everyday social interactions. Examples include riding a bus, purchasing groceries, attending a family dinner, being interviewed for a job, and going to a doctor’s appointment. Each of these events has its own set of social scripts. The things we say at a family dinner are different than what we say at a grocery store check out line.

A “social script” is a way people learn to navigate everyday social interactions. Examples include riding a bus, purchasing groceries, attending a family dinner, being interviewed for a job, and going to a doctor’s appointment. Each of these events has its own set of social scripts. The things we say at a family dinner are different than what we say at a grocery store check out line. You can download and tailor it to your child’s needs and interests. The document text can be edited and your child can draw your own pictures, or you and your child can choose photographs to put in the spaces above the text. The overall messages of these book are “My limb difference is a part of me, but not all of me. I can do all of the things I need to do and want to do, I may do some things differently from what you may expect.”

You can download and tailor it to your child’s needs and interests. The document text can be edited and your child can draw your own pictures, or you and your child can choose photographs to put in the spaces above the text. The overall messages of these book are “My limb difference is a part of me, but not all of me. I can do all of the things I need to do and want to do, I may do some things differently from what you may expect.”